Earning excess returns in commodities

Anatomy of an oligopoly

Say that we have an industry selling a commodity and we want to figure out how above average returns can be generated. Our starting point is almost perfect competition. We cannot create a brand, a differentiated product/service, a monopoly, a cartel or cheat.

To start earning an above average ROIC (of say more than 10%), prices need to be raised industry wide, or a cost advantage needs to be gained. In this article I want to take a closer look at how prices can be raised when no industry player has a real cost advantage.

Since cooperation is illegal, one company has to go first in raising prices, and hope the others will follow. Now say we have 100 competitors with 1% market share each and there are 115 units of capacity for 100 units of demand. Raising your price in this scenario is difficult. It will take time to ripple through to all competitors, and any one player can easily lose all their revenue before being forced to lower prices again.

Furthermore if a 10% market share player has much lower unit costs than 1% players, there is a strong incentive to not be left behind. And there will be a brutal struggle for survival until an equilibrium is reached where benefit from taking further market share is low.

Note also that this is a recursive process. Meaning that the first company to raise prices will look at what the payoff matrix is for the second potential company who would match their prices, instead of keeping them low to take market share. And the second will look at the third etc. Especially if there is a strong incentive to get lower unit costs, it is unlikely that this price increase will be matched by enough players, so there is no pricing power as nobody will be willing to raise first.

(Although usually in practice, instead of raising prices, a price increase at a certain date is announced to see if anyone follows with similar announcements)

Now take this scenario with only 3 players with 33% market share each, where unit costs will not become much lower by taking further share. With the same 115 units of supply and 100 units of demand, the risk is much lower for player 2 to follow player 1 in a price increase. As player 1 and 2 stand to lose at most ~7.5% of their revenue each if player 3 cheats (and if player 3 does not build more capacity). As opposed to a 100% revenue loss in the 1% market share scenario. And their price increase will probably make up for the market share loss in that case.

So it doesn’t really make sense to fight for more market share as the remaining players are strong enough to take back any lost revenue. And the threat of being squeezed out by larger players is gone. While the risk of raising prices is much much lower now.

This means the choice is now between fighting for market share and making a lot losses to only return to the same starting point. OR just raising prices and everyone makes more profit right away.

Where the upper pricing limit is set by barriers of entry and incentive to cheat is (mostly) gone.

The above description is just scratching the surface though. So I thought it would be useful to look at a real life example here: DRAM memory chips.

I made a check list of parameters for rating any commodity industry:

Geographical advantage

Economies of scale

Regulatory barriers of entry

Customer concentration

Cyclicality of demand

Ease of capacity exit

Time to bring on new supply

(Edit: I forgot the network effect, but that is not relevant in this article)

And please note that this is not a recommendation and I am not long any DRAM memory producer. It is more of a curiosity to try and figure out how game theory can be used to better understand oligopolies.

DRAM Memory chips

This is an interesting industry since it started out being consolidated and then deconsolidated, only to consolidate again about 10-15 years ago. In the 70’s Intel had 50% market share, but then the Japanese came in and in the 80’s and 90’s the Taiwanese and Koreans. With the number of players peaking around the mid 90’s when supply could not keep up with demand.

Then in the early 2000’s there was a rapid consolidation again as profitability was destroyed after the dotcom bubble due to overcapacity and slowing demand (source):

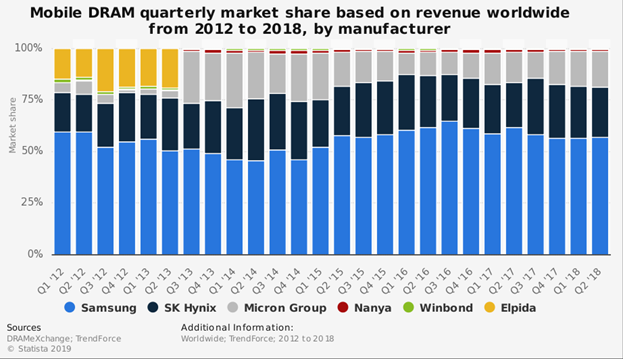

Between 2009 and 2013 it consolidated down to three main players, Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron (source):

Interestingly when Elpida was eliminated, the remaining DRAM players suddenly became very profitable as predicted in this 2013 VIC write up on Micron. Where the industry went from barely earning its cost of capital for several decades, with only occasionally some profitable years when demand was growing rapidly, to generating a (choppy) >10% ROIC from 2013 on. With a record number of consecutive profitable years.

And this transition was not gradual, but sudden, with the elimination of the last weak Japanese competitor, Elpida. Who was smaller in size than Samsung, SK Hynix or Micron. But much larger than Nanya. Despite that, Elpida gave up first. Possibly because the Taiwanese government was more determined than the Japanese one? Nanya’s share count went up more than 20x since 2005 and its financials were a trainwreck until 2013, when they signed a licensing deal with Micron:

Elpida’s financials looked much better than Nanya’s as they generated a positive operating profit of $500 million, at a margin of ~7% (source) in 2011. They did have $2.8 billion of net debt though, unlike the net cash positions for Micron and SK Hynix. And they had underinvested in the more niche NAND tech (basically flash memory).

So when in 2012 the DRAM market imploded they could not switch capacity to NAND to soften the blow. And Elpida’s shareholders, bond holders and the Japanese government simply had enough. Instead of buying more shares and diluting share count by >90% like with Nanya, they accepted bankruptcy.

Then when Micron bought Elpida out of bankruptcy, converted a portion of its supply to NAND and demand for DRAM recovered, profitability of the industry improved dramatically. And Micron shares went up more than 10x from the lows of 2012 over the next decade, generating a 30% CAGR.

Going through the check list

Now let’s have a look at what makes this industry tick by going through the above checklist of parameters. There is no geographical advantage here since value to weight ratio of DRAM chips is very high, so this is a global industry. Shipping costs are probably a rounding error.

Economies of scale are large in R&D spending, but relatively low in production. Nanya (the green line) is far smaller than the other two and it seems their lower gross margins were mainly due to their likely inferior outdated technology, and not from their much smaller production base:

Memory chips are not a static commodity, they are constantly evolving. If they fail to keep up technologically I guess you could say they become a commodity “commodity”? R&D costs have gone up by a factor of 50-60x per player since the early 90’s.

Looking at R&D spent in 2011 (I couldn’t find Samsung’s DRAM R&D spending):

SK Hynix spent $525m, or 5.8% of revenue

Micron spent $592m or 6.7% of revenue

Elpida spent $500m or 7.8% of revenue

Nanya spent $283m or 23% of revenue

So it seems that around 2011 the lower bar to keep up was roughly $500-600m of R&D. If you spent below that your tech would fall behind. If you spent much more than that your tech would advance before the next replacement cycle and there would not be enough demand.

Before the 2013 licensing deal with Micron, Nanya’s tech was clearly falling behind due to their lower R&D spending which was the reason for their lower gross margins (source):

As for the 2020 market share figures, I could only find Samsung chip R&D spent. But couldn’t find specific revenue figures, since a lot of them are produced for internal use (source):

Samsung spent $5.6 billion, but this was all chip R&D spent, not just DRAM, so probably < 10% of revenue?

SK Hynix spent $2.9 billion or 10% of revenue.

Micron spent $2.6 billion or 12% of revenue.

Nanya spent $182 million or 8% of revenue (but they still licence from Micron).

What can we conclude here? If you want to enter this industry you probably can’t easily licence technology from one of the major players, as they probably don’t want a new player entering the industry. So you have to spend at least $2-3 billion in R&D per year to keep up. Which means you need to take at least 20% market share right away to generate an attractive ROIC above 10% (or almost $50 billion of capital invested) at current prices. Which is of course difficult as a new 20% player would effectively destroy all profitability for the foreseeable future due to oversupply. So this creates very sizable barriers of entry.

Furthermore, it would be difficult to find the qualified people to spend that $2-3 billion of R&D on. Not like there are thousands of skilled DRAM semiconductor researchers and workers just idling around, ready for hire. So this would probably increase R&D costs for all players, requiring even larger scale.

Continuing down the list to regulatory barriers of entry. Usually this advantage comes in the form of environmental regulations like for example with pipelines. The DRAM industry scores very low on this, since that is not really a factor here.

As for customer concentration, DRAM makers get a low-moderate score. Micron’s largest customer is 13% of revenue. With Micron being 20% of the global market.

The memory chip industry has a high cyclicality of demand. So a low score. The more cyclical demand is, the more likely it is that capital destruction will occur in an industry. Because there is a risk that new players are lured in by excess profits and shortages. Unless built time for new capacity is very long, or barriers of entry are very high (which is the case here).

Ease of capacity exit is moderate-high now, but it used to be low. The difference is that now DRAM capacity can be converted into NAND industry wide. And with only 3 major players, supply can more easily be taken offline in times of over capacity. So this makes the high degree of cyclicality less problematic.

Time to bring new supply is only 1-2 years. So a low-moderate score. But again, if there are very high barriers to entry, it does not matter that much.

How did consolidation happen?

The problem with semi conductors is that the costs to generate the next generation of chips grows exponentially. Whereas revenue starts levelling off as the industry matures (source):

The largest player has the ability to set the amount of R&D that has to be spent to keep up. Where the upper limit is determined by the purchase cycle (takes some time before everyone upgrades their hardware again).

I think due to the lower complexity of memory chips compared to say CPUs in the early 90s, this number was not so high that there was only room for 1-2 players from the early stages. For example in 1993 Intel already spent close to $1 billion in R&D, while Micron only spent $57 million. So a difference of almost 20x. Whereas today the difference is 5x.

So as DRAM technology advanced and became more complex, the room for more industry participants decreased. This is probably why, unlike for example in the paperboard industry, profitability and ROIC did not steadily increase with consolidation.

And interestingly DRAM producers were accused of forming a cartel in the most unprofitable years (early 2000’s), and not in the more recent years which were far more profitable.

How durable is the moat?

I see quite a lot of risks here actually. The first and obvious one is the size of R&D costs. Either industry wide R&D costs will rise faster than total revenue, turning this into a duopoly or monopoly like industry where only one player can do well. Or the other way around, where a technology limit is reached, creating longer upgrade cycles where for example 5 or 10 year old DRAM tech is still good enough for most customers.

Currently Micron spends around 10% of revenue on R&D. If this number would lower to 3-4% in the future, it lowers the barrier of entry. As a new entrant would now only need to take 5-10% instead of 20% to have the R&D scale to compete.

Additionally, larger companies become more bureaucratic, lowering their R&D efficiency. Or they simply spend it in the wrong direction, allowing a more nimble competitor to take a different direction and build up a lead. I think this might have happened with Intel? For decades AMD was barely profitable and always catching up and Intel basically had a monopoly. But somehow AMD seems to have caught up and even overtaken Intel in some areas in the past couple of years. Rapidly catching up in revenue size with Intel. Despite spending far less on R&D.

Another risk is something that has already happened multiple times in the past, and that is that government sponsored players will enter the market. What if China decides that they need domestic DRAM production? They could throw up trade protection barriers and put up the capital needed to take 20%+ market share and flood the market. In one blow DRAM producers would lose one of their largest markets and gain a large competitor.

And that is my somewhat rambling take on DRAM chips and how companies in an oligopoly can earn excess returns selling a commodity. I wanted to analyze some other commodity industries as well, but this is getting a bit long. So if there is interest I can do the shipping, railroad or paperboard industry as well.

If you are curious about Micron or the DRAM chip industry in general, there are 6 write ups on Micron and one on Nanya on Valueinvestorsclub:

https://valueinvestorsclub.com/ideas

And the paper on Micron I used as source is also a good read:

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/4423431.pdf

I have no position in any of the stocks mentioned, and this is not investment advice.

Wow, I really e enjoyed and learned a lot with this article. I would love to read more articles like this (railroad or paper industries would be perfect, as you suggested). How long did you need to do such a deep analysis? Thank you for sharing your knowledge

Great writeup, I enjoyed reading it a lot! Railroad/paper industries would definitely be interesting as well, I'll be waiting in hopes you post about them too.